NB: I believe this topic has been discussed much better many times elsewhere on the net and in print. I am writing simply to clarify my own thoughts. I apologize for the primitive graphics.

In a previous post I examined block sizes for perimeter apartments, a common form of housing in Europe. They allow fairly high density, but generally don't allow for very large businesses to be established on their ground floors. Many businesses don't necessarily need or even want street-level access, and could occupy higher floors. Others want much larger floor plates, or need to be in a separate structure for reasons of noise, vibration, or other measures. Replacing the portion of the perimeter apartments with a building dedicated to businesses is one way to integrate the two functions.

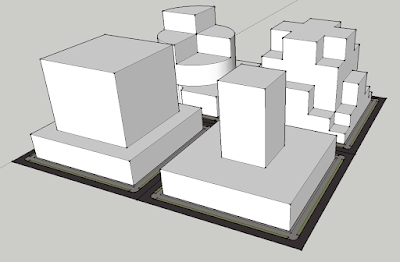

Here I have depicted some fairly simple divisions of a block into thinner perimeter apartments and commercial buildings that use up their entire lots. The main issue is the amount of open space from any window to a wall or window on a facing building. This is culturally dependent, and ranges from a few feet to as high as 80 feet, even in urban areas. New York City has codified a minimum of 30 feet from a window to a wall, and 40 feet from a window to a window, but only up to 25' in building height. Offset distances increase with building height. For a building 55' high, as I have been using, the values would be 50' and 60', meaning the commercial building in the upper left corner could not be inserted into the block without carving it back to the T-shaped area outlined on the roof. However, if it was built first to the limits of the lot, then subsequent apartments might have to be impractically thin. The zoning code may have rules for resolving, preventing, or mitigating conflicts of this kind, or it may depend on negotiation and trading of rights. No matter what the method, the conflicts would need to be resolved clearly. Otherwise, the first landowner to build in any block could seriously impact the use of every other owner on the block without the others' consent or foreknowledge. There would be less conflicts on blocks larger than the 260' by 260' (buildable) examples I have shown above.

For larger businesses, it may be necessary to develop entire block at one time, and replace the entire interior of the block with the commercial structure. This is often done with parking garages in suburban developments, and results in what has been dubbed the Texas doughnut. This configuration has the advantage of hiding pedestrian-unfriendly or generally unappealing buildings away from sight. Structures hidden in this manner can cut some costs since aesthetics are not a concern. However, the arrangement could reduce the exterior ring of apartments to outward-facing units only, meaning that common elements are shared between fewer units, increasing per unit costs. The density of the block would be less than with double-sided blocks, but the tradeoff may be worthwhile in some circumstances. With bigger blocks, it would be easier to develop a large commercial structure with little impact on adjacent buildings.

Another approach available only to large development projects is to stack the functions. By putting the business functions on the outside and constructing a residential tower above that on the inside, businesses could have fairly large floors. However, the apartments could possibly look out on an unattractive roofscape full of machinery, solar panels (hopefully), or highly reflective roofing material, though "green roofs" could be an option. They would also lose any connection to the street below, giving them a suburban feel at best. Inverting those functions would work better in some ways, with the apartments looking directly onto the street, and the businesses looking onto a relatively small roof area, along with the street, at least from higher floors. However, the major disadvantage here would be a large area of interior space below the tower that would have limited uses, such as storage or parking. Parking located here would be fairly expensive, as it would all be custom-designed and cast-in-place in order to fit inside the envelope and have a column grid compatible with the businesses above. More complicated architectural forms could potentially make the large interior area less useful, though they would benefit non-occupants if they had lasting aesthetic appeal. Overall, I think smaller blocks would work better for whole-block developments, but it would depend a lot on local expectations and regulations related to heights and setbacks.

In addition to businesses of various sorts, there are a number of other institutions that are part of any urban fabric, including religious organizations, schools, universities, hospitals, government facilities, and museums. All of those will have a physical presence. Often they are large enough to require an entire block, or are given one in order to highlight their prestige. But smaller institutional buildings can be easily integrated into a block of apartments.

Investigating the mixture of apartments with larger commercial or civic functions leaves less clear answers about block sizes, because the non-residential functions have widely varying needs. In most dense areas, I feel the established grid should force the commercial or civic function to adapt. There may be a few situations where institutions need to combine blocks to function effectively, such as sports arenas or conference centers. But those should be rare exceptions, and should be sited so the superblocks don't interrupt important traffic corridors or divide neighborhoods. In a future post, I will look at block sizes for larger businesses.

No comments:

Post a Comment