NB: I believe this topic has been discussed much better many times

elsewhere on the net and in print. I am writing simply to clarify my

own thoughts. I apologize for the primitive graphics.

In a previous post I examined block sizes for perimeter apartments, an arrangement found in Europe that can create high-density neighborhoods. In this post, I will look at other high-density apartment building types, mostly from New York City.

NYC has been America's most populous city since the first census in 1790, and contains one of the largest extents of hyperdensity on the planet. Due to the restrictions imposed by the surrounding waterways, land has long been valuable in the city, leading to intensive development. When the majority of the Manhattan was laid out in 1811, the population was only about 100,000. In contrast, London had a population of about 1,200,000, and Paris about 600,000. The blocks in the undeveloped parts of NYC were divided mostly into lots measuring 25' by 100'. This was deemed appropriate for a single-family house at the time, whether attached or detached. However, as the city grew rapidly to 810,000 by 1860, the lot width became a liability, because the single family houses were replaced with tenements, or apartments, for low-income residents, which were the majority of the population. The earliest of these ("pre-law") were often built to the limits of the lot, with only a 10' deep rear yard. This meant that interior rooms received no light or fresh air, as light shafts or courtyards would cut into profits of the landlords

This led to the "First" Tenement House Act of 1867, which required fire escapes for each apartment and windows for each room, among several requirements. Landlords met the letter of the law by installing windows in interior walls, which may have provided a slight improvement for some rooms, but was not what the legislators had intended. In 1879 the "Second" Tenement House Act was passed, which required windows to face the street, a yard, or a minimal airshaft open to the sky. This airshaft was very small by design, to please developers, and did little to light rooms. Unfortunately, the narrow air shaft led to two problems. One was that it was used as a dumping area for trash and waste by residents on upper floors, leading to unpleasant odors for all because the space was not designed to be easily accessed for cleaning. The second was that it enabled fires to spread floor-to-floor and building-to-building more easily, as the air shaft acted as a flue.

The problems with the "Old Law" led to the "New Law" formally known as the New York State Tenement House Act, passed in 1901. This new legislation required "inner courts" entirely enclosed by the property to be at least 24' by 24' for a 60' tall building. For courts on lot lines, the minimum was 12' by 24', which could be paired with the adjacent building for a more open space. The law also allowed "outer courts" to extend from deep inside the building to a street or back yard. These had an minimum dimension of 6' when on a lot line, and 12' when between parts of the same building. The measurements again were for a 60' tall building. The regulations for both inner and outer courts had adjustments for both taller and shorter buildings, as well as absolute minimums.

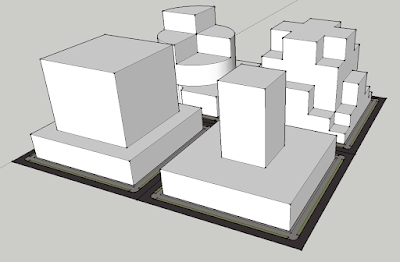

Above I have depicted the basic shapes allowed in each era. First, at the bottom, are the "pre law" tenements that were allowed up to 1879, with no air shafts at all. Next are the "old law" "dumbbell" tenements, with the problematic narrow air shafts. On the upper block are examples of inner court and outer court "new law" buildings. Multi-family dwellings on lots under 40' or so became much more difficult to build economically after passage of the law, thus the wider buildings. Pre law and old law tenements were mostly 4 or 5 stories in height, but some new law tenements were as much as 6 or 7 stories, even without elevators, in order to make up for the lot space reserved by the new requirements. Similarly-sized buildings conforming to the 1901 statute were also constructed for more upscale customers, with larger suites and at least one elevator.

Another major city experiencing explosive growth about the same time was Berlin. Previously the capital of Prussia, it was made the capital of a united Germany in 1871. The population then grew from 826,000 to 1.88 million by 1900, roughly the same as Manhattan at the time. It also had tenements, known as mietskaserne, or "rental barracks." These buildings may have started as perimeter blocks, with additional structures added first at the rear of each, and then along the sides, to create large interior courts. But by the late 1800s, they were regularly built to the lot line from the start. Unlike in NY, there were not separate buildings for the wealthy and the poor. Instead, the wealthy lived in the front section on the second floor, while others crowded into the rest of the building. Blocks in Berlin are much less regular than in Manhattan, and the image above shows an abstraction of the basic form. The mietskaserne were often extended to create a second or even third courtyard on deeper blocks. This did not happen to tenements in New York, because the more rigid street layout created few deep blocks. The meitskaserne could also be reoriented to pair with units on the opposite side of a very shallow block Also included in the image for comparison is a block with identical dimensions and perimeter apartments.

|

Perimeter, 60' thick |

25' Pre-law |

25' Dumbell |

50' New Law I-plan |

50' Mietskaserne |

| Gross length |

900 |

900 |

900 |

900 |

900 |

| Gross depth |

260 |

260 |

260 |

260 |

260 |

| ROW width |

60/100 |

60/100 |

60/100 |

60/100 |

60/100 |

| Net length |

800 |

800 |

800 |

800 |

800 |

| Net depth |

200 |

200 |

200 |

200 |

200 |

| Lot width |

580 |

25 |

25 |

50 |

50 |

| Lot depth |

130 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

| Lots per block |

2 |

64 |

64 |

32 |

32 |

| Units per floor |

100 |

4 |

4 |

6 |

7 |

| Floors |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

5 |

| Lot coverage |

66.00% |

90.00% |

78.00% |

68.00% |

72.16% |

| ROW per unit (ft.) |

2.32 |

1.81 |

1.81 |

2.42 |

2.07 |

| Density per block (pers./sq. mi.) |

119,138 |

152,497 |

152,497 |

114,373 |

133,435 |

Because of their very high lot coverage ratios, the pre-law and dumbell tenements generate the highest density. New law buildings cover less of their lot, which accounts for the lower density. However, they are by all accounts much more pleasant to live in. An argument can be made that the mietskaserne are better still, because they have one large courtyard instead of a smaller courtyard and a rear yard that isn't very usable. They are the only type still built as well, as the NYC zoning code has continued to be updated and nothing in the shape of the new law tenements is built. Block sizes for the mietskaserne should probably be driven by a balance of walkability and efficiency, similar to perimeter apartments. The NYC blocks are too long, so something around the size I have previously been using (580' by 240' buildable) would preferable. However, some blocks with mietskaserne in Berlin are as large as 700' by 800', with over 35 interior courts. That level of interaction between different structures might be a difficult to sustain in societies where businesses relationships tend to be more adversarial.

Much larger buildings were also constructed within the regulations of the 1901 law. Show below are three whole block buildings. From smaller to larger they are The Apthorp (1908), The Belnord (1909), and London Terrace (1931), which is actually 14 adjacent buildings. The first two are luxury buildings with large units and separate servants' elevators and entrances. The last was designed as a middle-class housing for workers in Midtown Manhattan. Its units ranged from studios to two bedroom units, with some larger penthouse units. Originally housing over 4000 residents in 1665 units, it remains one of the largest apartment buildings in the world.

Filling a lot right up to the edge of the surrounding right of way is not the only way to create density. Isolated towers can be constructed with enough floors to substitute for high lot coverage. In fact, that was the point of one of the earliest proponents of the "tower in the park" arrangement, Charles-Edouard Jeanneret. However, in reality most residential towers aren't surrounded by parkland, but parking garages, indoor malls, or other pedestrian-unfriendly features. In some cities, most notably Vancouver, the towers are located in or on a podium of human-scaled shops and housing, but that arrangement is not the rule. Isolated towers in NYC, whether privately or publicly-owned, are usually not surrounded by other buildings. But neither do they float in a sea of undisturbed nature; land there is too valuable to allow that. In most cases the spaces surrounding NYC towers are simply small sections of fenced-off grass, with a few trees and not a lot of other landscaping.

|

Perimeter, 60' thick |

Belnord |

London Terrace |

UdH-style towers |

HK-style towers |

| Gross length |

900 |

440 |

900 |

900 |

900 |

| Gross depth |

260 |

260 |

260 |

260 |

260 |

| ROW width |

60/100 |

60/100 |

60/100 |

60/100 |

60/100 |

| Net length |

800 |

340 |

800 |

800 |

800 |

| Net depth |

200 |

200 |

200 |

200 |

200 |

| Lot width |

800 |

340 |

800 |

800 |

800 |

| Lot depth |

130 |

200 |

200 |

200 |

200 |

| Lots per block |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

6 |

| Units per floor |

100 |

18 |

100 |

40 |

8 |

| Floors |

5 |

12 |

16 |

23 |

36 |

| Lot coverage |

66.00% |

68.61% |

60.40% |

25.50% |

21.14% |

| ROW per unit (ft.) |

2.32 |

6.48 |

1.45 |

2.52 |

1.34 |

| Density per block (pers./sq. mi.) |

119,138 |

115,803 |

228,746 |

109,607 |

205,871 |

There are a two things to note in the table above. First, the densities of both The Belnord and the London Terrace complex are based on census data, instead of being calculated. Because they are expensive properties, they may have a higher number of small households and second homes than the rest of the city, so the density shown is probably lower than I would calculate. Unfortunately, I don't have access to current floor plans, so calculation is impossible anyway. Second, the block sizes for the two tower-style buildings are arbitrarily the same size as the others, which affects the density calculations. In reality, because they are intended to have little relation ship with the streets below, block sizes don't matter that much. The vast majority of similar towers have been built in China, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Korea, where they are part of large planned unit developments (PUD), and have a very suburban feel. That is unlike The Belnord and London Terrace, which arguably may overwhelm their adjacent streets, but don't entirely turn their back on them.

Ideal block sizes for the isolated tower blocks are essentially impossible to determine, because of their lack of relationship to surrounding streets. Preferably, they would not be built in an urban environment, but in NYC many have, often arranged in geometrical patterns on superblocks that obliterated existing streets. For the whole block-buildings, a shorter block works better because it promotes walkability. London Terrace should have been be split between two different blocks, and have more retail or office space on the ground floor, but NYC does not have a history of splitting large blocks to this day. The depth of the block for the three probably depends on what people feel about the tradeoff between density and light. North-facing exposures on lower floors will never get much natural light, but somewhat deeper blocks would increase the amount. The tradeoff would be lower density and higher land costs per unit.

At this point I have explored most housing types that are built in high and middle-income countries. In a future post I will look at some commercial structures and whether then can be constructed within the confines of a urban grid.